How companies shake off the shackles of bureaucracy and become fit for humans and fit for the future

4 January 2022

1. Bureaucracy kills customer and employee proximity

History has taught us that it is important for organisations to employ stable, precise and stringent processes to achieve reliable results. This thinking dates to the beginning of the 20th century when people were perceived as production machines and were not expected to think for themselves.

The idea of bureaucracy has taken hold in organisations. At first glance, this may not seem to be a problem, and yet the organisational form must always adapt to the environment and not vice versa. It is precisely in these volatile, uncertain, complex and ambivalent times that the question arises as to what companies should look like to be more responsive to the demands of today’s employees and will therefore be more successful in the long term.

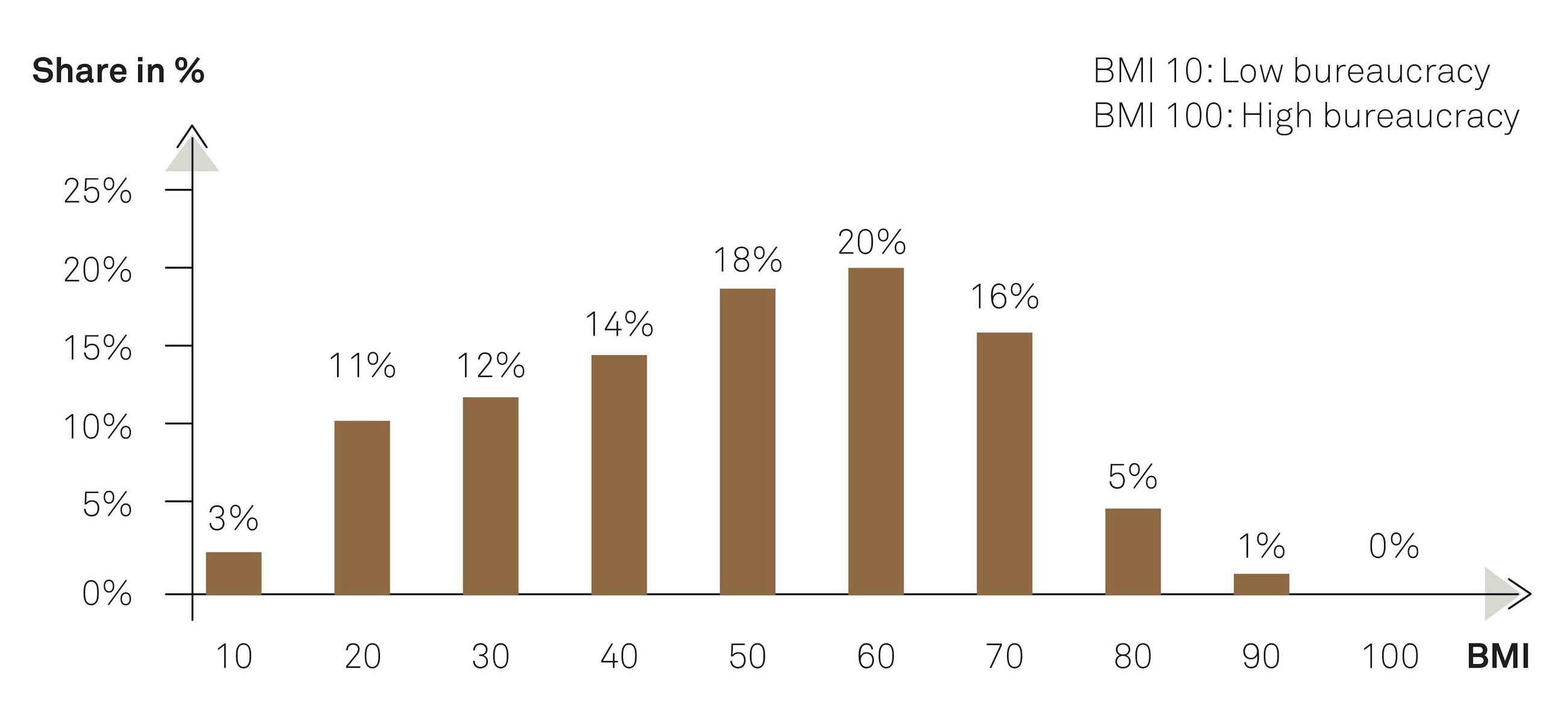

Many companies and their front-line functional units are too bureaucratic. Hamel and Zanini reached this decisive conclusion in their global studies on bureaucracy, developing a new measure: the “Bureaucracy Mass Index” or “BMI” for short.

Employing ten questions (figure 1), they assessed companies’ levels of bureaucracy (measured on a scale from 1 to 100; 100 = highest level of bureaucracy, 0 = lowest level of bureaucracy).

On average, about a quarter of our working time is spent on internal and external compliance without any economic value being added or customer benefit being created. On top, it is alarming to note that studies show an increase in bureaucracy in companies year over year. This raises the question of the extent to which bureaucracy can be eliminated to improve the performance of companies.

This question was also the starting point for the collaboration between the Swiss Marketing Association (German: Gesellschaft für Marketing) and Implement Consulting Group, which ultimately led to the implementation of a study in Switzerland. By interviewing 120 sales and marketing executives, we determined, among other things, the BMI of the respective companies.

The Bureaucracy Mass Index (BMI)

In their book Humanocracy, authors Hamel and Zanini operationalise bureaucracy using the following elements:

- The number of organisational levels between CEO/GF and front-line organisational units.

- The time spent on bureaucratic tasks such as filling out reports, compiling lists etc.

- The extent to which decision-making is slowed down by bureaucratic processes.

- The number of meetings and work preparations initiated by superiors.

- Autonomy, geographical distance and lack of cooperation among front-line organisational units.

- Integration of employees active in front-line organisational units in the implementation of practical changes.

- Employees’ reaction to surprising or unconventional ideas – enthusiasm versus resistance.

- The process of launching a new project, especially the financing of a small team.

- The nature of the internal political procedure to enforce a decision.

- The requirements towards the employees’ political skills to advance in the organisation.

Source: Hamel/Zanini (2020): Humanocracy

With a median score of 48 points measured on a scale from 1 to 100, Swiss companies can be described as moderately bureaucratic. Only a few companies show a low BMI and therefore a low level of bureaucracy while there are still many companies with a high one (figure 2).

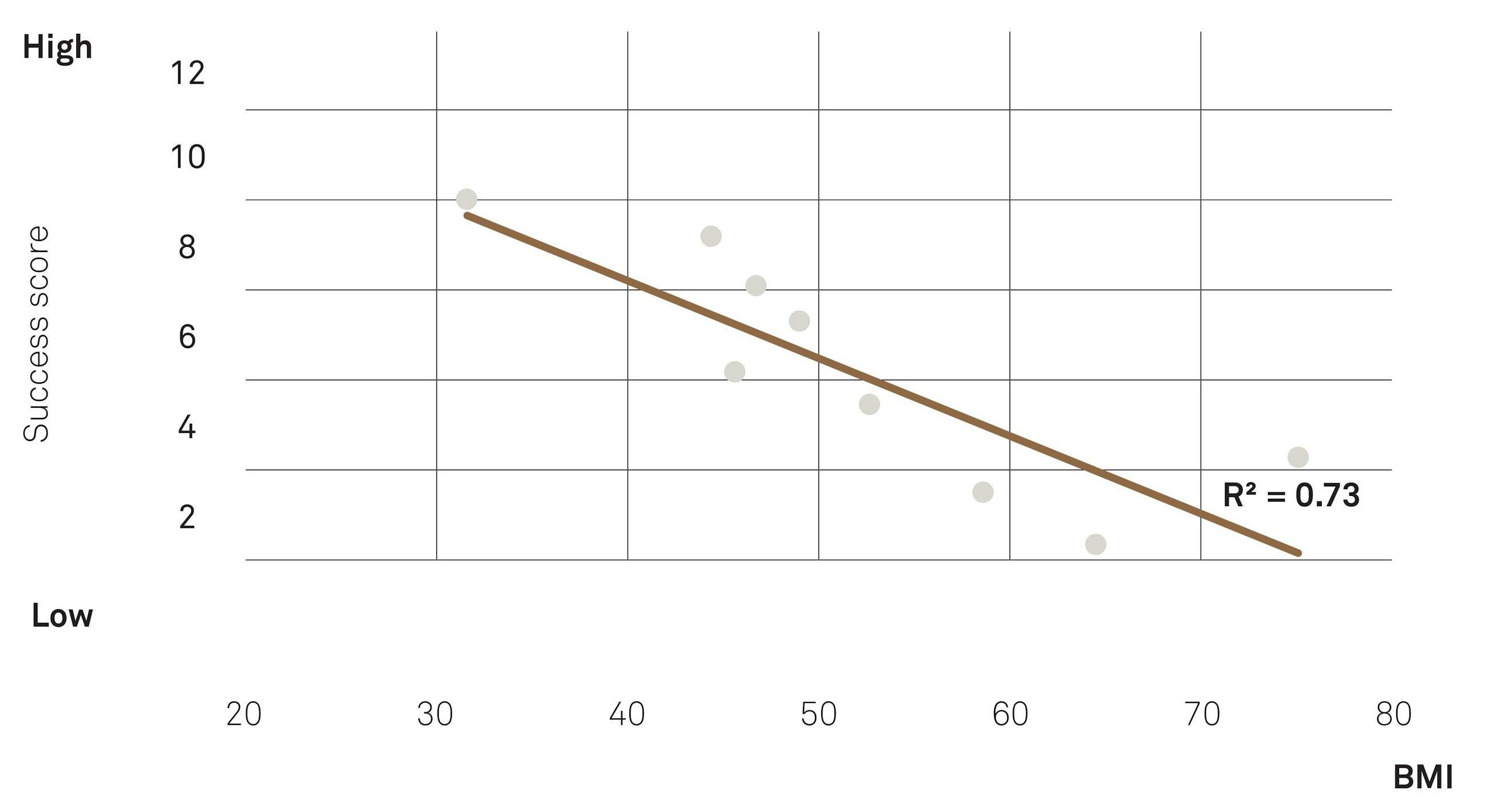

Comparing the determined BMI values with the respective companies’ economic success (sales and profit growth in the last five years), a clear result emerges: the lower the level of bureaucracy, the greater the economic success (figure 3).

Above all, non-bureaucratic companies are more accurate in recognising customer needs and are faster and better in translating the knowledge gained into products and services. Conversely, this implies that bureaucracy is a major impediment to the performance of frontline functions.

Given these results, we investigated the following questions:

- What is the level of bureaucracy in Swiss organisations, and where do we see the biggest room for improvement?

- In which aspects do successful companies function less bureaucratically than others?

- What does an operating model look like that is “fit for humans and fit for the future”?

- How can the transformation to a post-bureaucratic company succeed?

2. Five core principles to become fit for the future

What needs to be done?

What steps should companies take to become fit for the future? Four seemingly simple but difficult-to-implement principles must be realised

No. 1: Focus on needs

Customer focus is a generally accepted and self-evident principle. As emerging customer needs and expectations are usually not visible, aligning corporate value creation with them is difficult. In fact, customers may not even be aware of them themselves. The aim is to fulfil “unmet needs” far beyond the profile of existing customers as well as to identify potential customers at an early stage and incorporate them as a guiding principle in all commercial decisions.

Example: By consistently focusing on the pain points of smartphone users (as well as the in-store experience), Apple managed to outpace various competitors for a long time. The focus lies on the reason WHY someone does something rather than the WHAT or the HOW.

Employees from all areas, especially those involved in innovation, marketing and sales, need to work as close to customer needs as possible and share their knowledge and experience through seamless, institutionalised collaboration.

Example: Haier calls it “creating zero distance” between employees and users of their home appliances, making the flow of information inevitable.

So, in terms of customers, there can only be one metric. If the product or service is recommended, one can speak of genuine customer satisfaction. The consistent orientation towards the Net Promoter Score (NPS)1 reflects this fundamental attitude. As customers’ expectations and demands vary, flexibility and autonomy are needed – precisely where customer and product decisions are taken.

Compliance with bureaucratic guidelines, rules and regulations impedes customer proximity. Processes should therefore be geared more closely to customers and their needs. The gold standard NPS is closely intertwined with the performance management system.

Example: NPS is used by California Closet, among others, as the leading management tool. California Closet is characterised by a high NPS of 85+ and considers this value as a starting and reference point.

No. 2: Embrace uncertainty

Organisations are aware of the need to change, to transform, to become different in order to respond in an agile way to the challenges they themselves recognise as volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA). Most companies know that in this VUCA world, their traditional way of doing business could be disrupted and challenged by new competitors – and even more so by the emerging needs of a next generation of customers inspired by different values, enthusiasm for technological innovation and a new sense of entitlement.

Management must systematically promote awareness of permanent change. Employees should not perceive adaptation and transformation as a threat but as a pleasure principle of entrepreneurial action.

Furthermore, they should be prepared for changes in context. Rita McGrath calls it “seeing around corners”. In this regard, a large number can foresee more than just a few.

Especially in marketing, where two-thirds of the action now happens “without us”, i.e. we have relinquished control, we need to implement new principles like experimentation.

Successful companies have learned to integrate uncertainty and unpredictability into their corporate culture. In iterative and creative processes with intensive feedback on prototypes, Design Thinking proves to be a suitable instrument for developing new solutions. The concept has proven itself in a dynamic world to such an extent that it has long been used in strategy work, the development of new value propositions or adjustments to the operating model.

Example: Already some time ago, PepsiCo introduced the role of the global Chief Design Officer whose task is to transform the comprehensive product range of the entire group with principles of human-centred design.

No. 3: Foster autonomy and proactivity

Just 34 percent of employees describe themselves as motivated or not apathetic. Meanwhile, 60 percent of transformation projects in companies fail. Although these projects may be correctly identified, they are not successfully executed and implemented. The level of bureaucracy is to a large extent the main reason for both, as inner distance from work and a correspondingly high level of frustration cause employee engagement to atrophy.

By contrast, maximum personal responsibility, defined autonomy and inspiring leeway promote employees’ entrepreneurial skills and their motivational power.

Example: We can learn from Spotify how to balance employee autonomy and accountability when it comes to balancing creativity and engagement with clarity and efficiency.

For companies to transform their employees into sources of entrepreneurial success, they must be empowered and encouraged in terms of autonomous action within the organisation. The focus on proactive employees also affects anxious colleagues: “insecure dawdlers” will sooner or later be repelled from the habitat of autonomous employees and leave the company. The proactive employees will quickly focus on the needs of future customers – and they will do so with pleasure, which in turn will be intuitively registered by the customers. Such employees must be closely and directly confronted with the value propositions, which in turn requires an agile and flexible working environment.

Example: There is a close correlation between customer NPS (recommendation as a supplier/ service provider) and employer NPS (recommendation as an employer). Companies such as California Closet, Spotify and Netflix have implemented this insight in their organisations.

No. 4: Establish marketplaces of ideas

Markets are more capable of balancing needs and resources than centralised control mechanisms like top management. When areas such as marketing, sales or customer service are exposed to competition with external providers or similar units within the organisation, oftentimes better results emerge. A market leads to the retention of internal departments only if there is an internal demand for them.

Example: At Haier, the world’s largest home appliance company, competing marketing, sales, service and design teams support the 200 market-oriented teams. Competition ensures that new teams are constantly entering the internal market with offerings that are increasingly well adapted to needs.

Original ideas from different providers are developed across company boundaries, which can lead to innovative solutions, e.g. by combining different technologies. The marketplace calls for different actors who can implement technology convergence2 with their various skills and experience. Social media experts meet marketing specialists, data-savvy engineers meet TV professionals, financial experts meet market researchers. In agile organisations, employees operate in ecosystems of this kind, where they are inspired by marketplaces of ideas daily.

Example: Uber is a striking example of this, since the company was only able to establish itself on the market through the combination of Google Maps, credit cards and other external functions.

It helps to use collective intelligence within the organisation in order to be able to make better decisions, especially in the case of critical problems.

Example: At Körber Digital, any employee can pitch a new product idea. After evaluating it, the whole company decides on the realisation of such new business ideas. The demand to reduce bureaucratic excesses therefore falls short as it is too imprecise. It is much more a matter of focusing on needs, embracing uncertainty, fostering autonomy and establishing marketplaces of ideas.

Although these are generally accepted requirements, reality paints a very different picture. It can be assumed that it is difficult for organisations to integrate principles, that are in themselves self-evident, into their organisations, even though they aim at achieving meaningful corporate goals with them. Rather than the WHAT, it is the HOW that has become the central challenge.

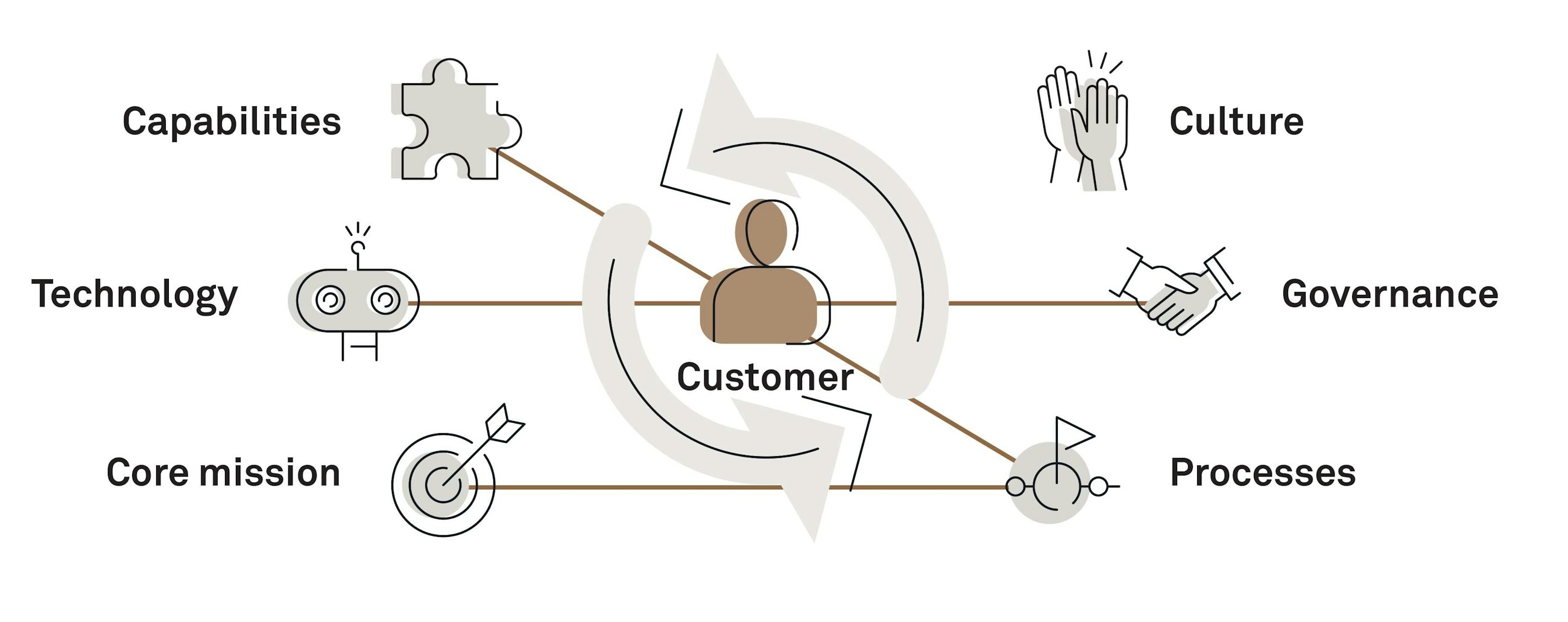

3. Seven elements lay the foundation of the operating model

The questions of how a sustainable organisation should be structured, what goals it should pursue, and what principles should be anchored in it. A company lays the foundation for answering these questions with its operating model (figure 5) – in other words, the way in which a company functions in order to generate added value for customers and employees. In this regard, principles and ways of working are more important than the organisational structure or fixed rules.

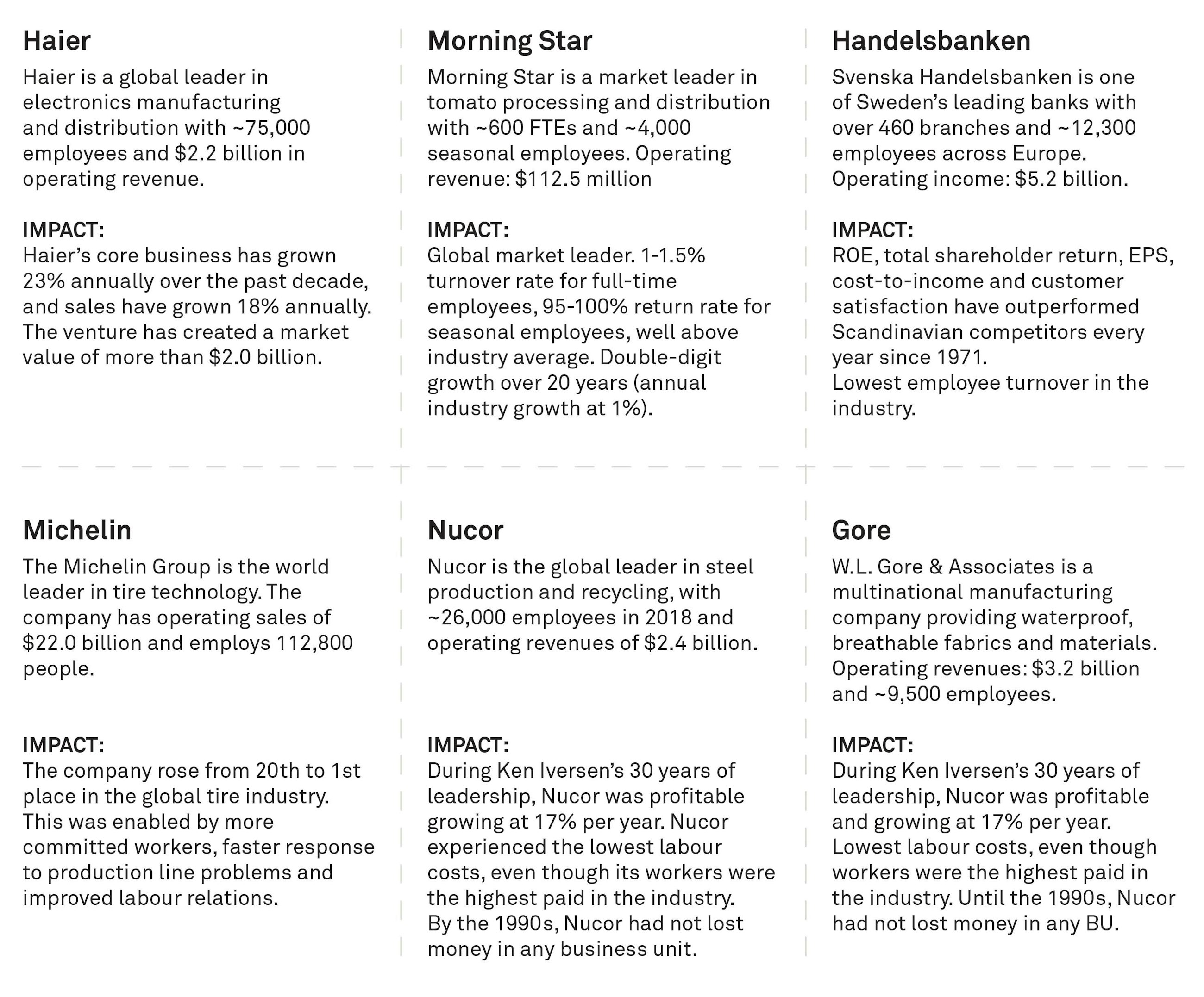

Figure 4 shows several pioneering companies that have recognised and understood the principles discussed above and have restructured their organisations accordingly. This resulted in a massive reduction in bureaucracy and, at the same time, a remarkable increase in performance.

Their focus was not primarily on financial success. What these companies have in common is that they have radically changed the way they work and deal with employees – especially in their customer-facing functions.

How does the reduction of bureaucracy succeed, and what does it require?

The post-bureaucratic operating model

A post-bureaucratic operating model consists of seven design elements, each of which can develop its full effect when properly coordinated with the others. By designing the elements according to clear design principles for post-bureaucratic companies, they meet the requirements of new market conditions as well as those of demanding employees. In the following, the aforementioned seven elements are presented and illustrated with concrete best practice cases.

Core mission: Everyone owns the purpose

The core mission defines the purpose of a company and thus the answer to the question of what added value is provided for which customers or other stakeholders. In classic companies, the corporate purpose and the core value proposition are often specified top-down. Not only does this approach result in a loss of proximity to the customer, but it also usually leads to a loss of identification and dedication on the part of the employees.

Unlike the classic operating model, in a post-bureaucratic company each person is granted autonomy and financial incentives allowing them to see themselves as the owner of the core mission and to act accordingly.

The target oriented mode of operation is ensured by setting up team oriented success calculations. These are linked to the core mission, whereby teams bear full responsibility and decision-making power.

Example: In Switzerland, Spitex, an outpatient care and housekeeping organisation, has improved its patient and employee satisfaction through self-responsible teams. These teams now have a performance mandate, a defined goal, as well as the responsibility and the authority to execute assignments and schedule work.

Processes: Experimentation as a philosophy

Processes serve to standardise, from the execution of tasks, to the creation of products and services, to the further development and optimisation of the company. The underlying premise is that the environment is known and static, so that standardised planning would appear to make sense.

In post-bureaucratic companies, processes continue to be important. However, they are designed in such a way as to encourage experimentation with new approaches and solutions. This allows complex problems to be solved in new ways. Every company is thus able to reinvent itself on an ongoing basis.

Companies that have defined experimentation as a core process go so far as to ensure that it is not the plan or the business case that decides whether ideas or projects are pursued but successful experimentation.

Example: The Bank of New Zealand gave its branches a high degree of autonomy, allowing them to adjust their opening hours to regional needs (e.g. branches with a ski resort nearby open in the evening, while others near a farmers’ market open on Sunday morning). The proximity to the customers also inspired new offers, for example a mobile trailer bank. Due to the diversity of ideas, the initial mistrust at the bank’s headquarters quickly disappeared.

Governance: Decision-making close to customers and employees

Governance defines how decisions are made and by whom. In a post-bureaucratic organisation, this means that decisions should not be guided by rank or political competence but rather by the talent, skills and performance of the individual. Governance thus functions as a meritocracy.

In concrete terms, this means that an employee’s decision-making ability should always be considered in its thematic context. Thus, the competence and performance rating of a colleague, for example, could be significantly higher than that of a former cadre member. This grading of decision-making capability is based on peer reviews and transparent to all employees.

Example: With the introduction of the “Responsabilisation” system, the Michelin Group engages its employees by enabling decisions to be made at employee level, while strategy decisions remain at group level. Since then, Michelin has risen from 20th to 1st place in the global tire industry.

Structure: Small, competent, customer-focused and empowered teams

The structure defines the functions and roles as well as the division of tasks and responsibilities in the organisation. In post-bureaucratic companies, customer needs gain even more prominence. Small, autonomous teams that make complex decisions in real time close to the customer can gain a better customer understanding.

Example: Nuuday, the front-end organisation of the Danish telecom company TDC with many consumer brands, simplified its organisation by reducing the hierarchical levels from five to three, forming 200 end-to-end teams responsible for a large part of the customer journey – from online ordering to home installation.

The organisation has thus become more customer-oriented and regularly achieves a very high NPS of over 30. Nuuday is considered one of the most popular employers in Denmark.

Capabilities: Curiosity and openness as the highest good

Capabilities refer to the competencies that an organisation must develop to meet the needs of customers and to distinguish itself from the competition. In a modern and non-bureaucratic organisation, curiosity and openness are celebrated as core competencies needed to develop and implement brilliant ideas.

As a result, dissenting opinions are not only tolerated, but quite specifically encouraged.

Example: W. L. Gore & Associates, as a lattice organisation, follows the four guiding principles of fairness, freedom, commitment and waterline. The waterline principle calls for the involvement of many stakeholders before a decision is made that would metaphorically “shoot under the waterline of our ship”.

Culture: Psychological safety and trust are a must

Culture is the guiding compass of an organisation and is based on a shared pattern of thinking, feeling and acting. In a post-bureaucratic company, culture is the most important good besides the customer and promotes a trusting relationship between employees. It promotes acceptance and psychological safety and thus the freedom to fully unfold the “I” and to contribute to the work environment.

Example: Netflix clearly demonstrates the importance of a shared mindset: Values such as the will to make an impact, unprejudiced curiosity, enthusiasm and honesty have in Netflix’s self-assessment significantly contributed to a shared mentality and thus to its outstanding performance.

Technology: Automatised administration and autonomy through digital systems and processes

Since the beginning of the pandemic at the latest, organisations and employees have been aware of the importance of digitalisation. Digital systems and processes manage to reduce administrative tasks to a minimum by taking over routine tasks. As a result, employees can focus on creative and challenging tasks, and corporate development and customer needs are better addressed with the help of the transparency created.

Example: Belgian FPS Social Security has a strong focus on deliverables rather than actual time spent in the office. The digitalisation of systems and processes has allowed remote working and employee autonomy. Step by step, the formerly unpopular employer developed into the organisation with the lowest absenteeism rates.

4. Top performers lead the way

GFM study profile (2021)

In the Swiss survey, approximately 120 marketing and sales executives were asked about their business success, the company bureaucracy and the parameters of the operating model. Besides presenting the current situation, we focus on the potential and the discrepancy between successful and unsuccessful companies with regard to their operating model.

Accordingly the following key parameters were measured:

- Success score: The companies’ success was measured on the basis of sales and profit growth. In order to determine the current status and a suitable classification, the five-year development as well as the industry benchmark were taken into account. Our sample resulted in a classification into low (n = 16), average (n = 49) and high performers (n = 49).

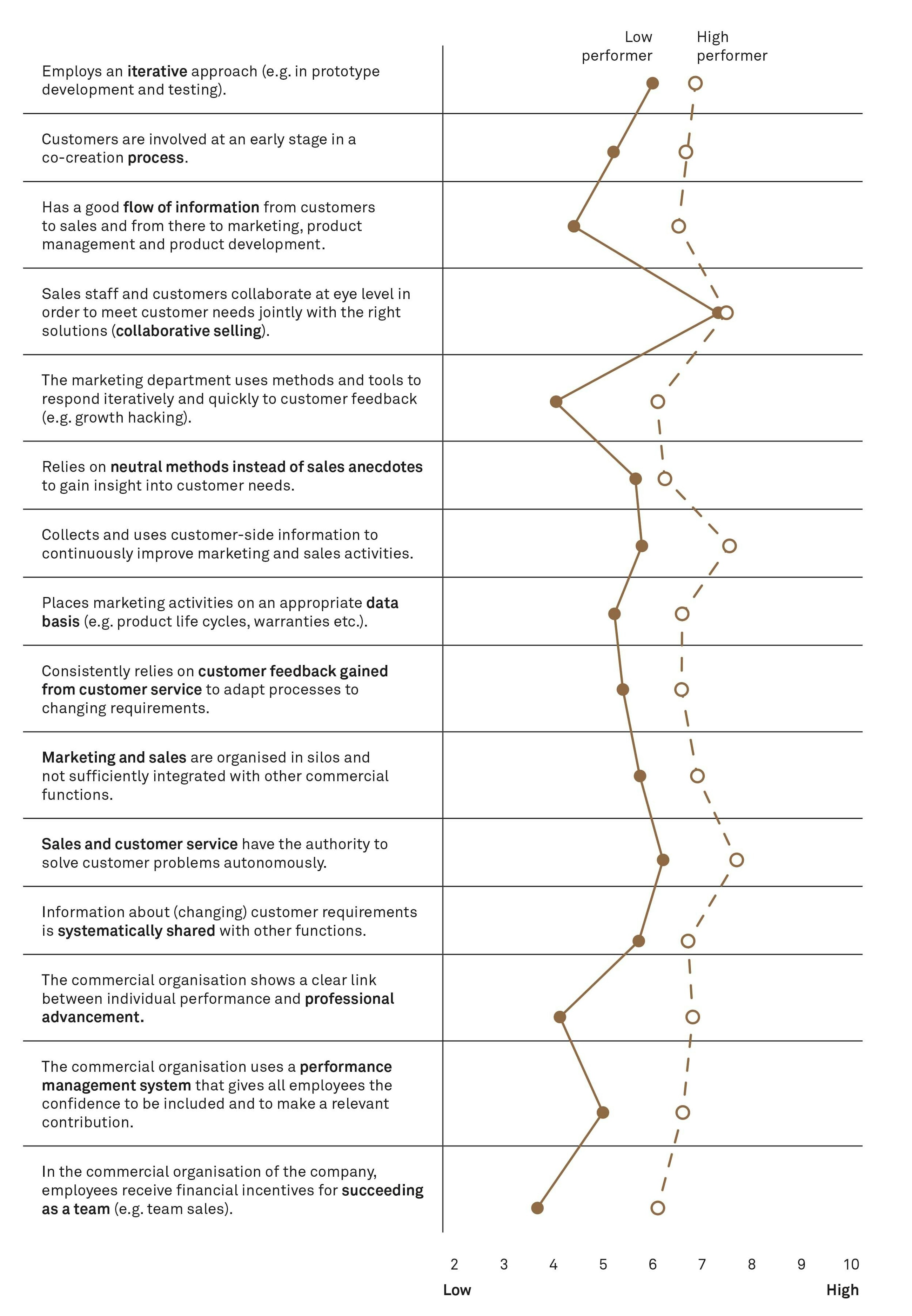

- Operating model excellence: Operating model excellence is a measure comparing the existing working practices in the sales and marketing organisation with the ideal post-bureaucratic operating model. To this end, 15 pertinent questions were formulated, and the respective answers were measured on a scale from 1-10 (1 = does not correspond at all to the target operating model; 10 = corresponds to the target operating model).

- Bureaucracy Mass Index (BMI): The BMI was determined by Hamel and Zanini employing the established ten questions (see figure 1). The focus of the study is the comparison of the operating model excellence of low and high performers.

In the empirical part of the study, we aim to show the correlations between success, bureaucracy and operating model excellence, focusing in particular on the exploited and unused potentials for companies.

Results:

What are successful companies doing differently?

Two important findings can be shown or proven by measuring operating model excellence. On the one hand, it is clear from figure 6 that low and high performers differ significantly in almost all criteria. High performers tend to have a more pronounced post-bureaucratic operating model across all criteria. This clearly shows the advantages of the post-bureaucratic operating model.

On the other hand, empirical research shows that even high performers still have significant potential for improvement and success. While the average rating of operating model excellence for low performers is 5.3, high performers also have room for improvement with an average rating of 6.7.

The details show what top performers do better than low performers:

Information flow

The flow of information between the relevant commercial departments (e.g. product management, customer service, branding and sales) functions smoothly and quickly. Silos are avoided as far as possible and reduced in favour of the common goal of customer satisfaction.

Experimentation

Feedback from customers, partners or employees is methodically collected, evaluated and iteratively processed in a continuous improvement process. Growth hacking, Design Thinking and the like are widely used. The operating model is not designed for administration but for permanent improvement of all elements.

Career prospects

The contribution of the individual marketing/sales employee leads to better career prospects – corporate policy and pure number optimisation are secondary. The energy and motivation of employees are not wasted on career optimisation but are channelled into value-creating projects.

Team incentivisation

In sales, employees are incentivised as a team – lone wolfism leads to self-optimisation, and customer needs fall by the wayside. Top performers carefully weigh individual short-term financial goals against long-term company goals.

Also, in the eleven criteria measured above and beyond this, the top performers are characterised by better communication, collaboration and agility as well as more pragmatism.

5. Top-down and bottom-up leadership initiates the transformation

The requirements for a future-proof organisation seem to be high, and accordingly, many companies may be reluctant to embark on major transformations. The following reasoning should encourage to set out on the journey nevertheless and thus to tap into some of the described benefits.

The transformation is to be understood and created as a movement. Start small, build momentum and continuously achieve small successes.

Experience shows that the project must be approached top-down and bottom-up simultaneously.

You cannot do it without top-down control. In at least three respects, a movement also requires a minimum of central control:

- Develop a shared ambition for the goal and journey (often called Northstar). Emphasise the WHY – what makes this ambition and journey important and right for everyone?

- Get the leadership team behind this ambition and ensure that they stand up for the chosen path at all times.

- Establish a new understanding of leadership, if necessary.

The movement’s power is developed bottom-up. This involves the following:

- Identify and start little flames/initiatives within the organisation in order to spark a wildfire in the medium to long term.

- Adopt best practices from different departments and teams.

- Support the scaling of initiatives by the leadership team. Get movement going by making flames bigger and successful, and planting and driving them elsewhere in the organisation – start small, scale fast.

In order to gain clarity about the starting point of the journey, it has proven useful to assess the organisation. Management is often surprised to discover how many small fires are already burning in their organisation, which now need to be fed with more oxygen and allowed to spread. For the assessment, the BMI instrument presented here is suitable, for example, as it initiates a very simple discussion. More courageous companies start with a management model hackathon or an action to detox their project and change engine.

Any attempt to launch an initiative towards a post-bureaucratic enterprise should be supported. The results at all levels show that the journey will be worthwhile.

Reach out to our experts

About Implement Consulting Group

The findings presented in this research series and supported by the study stem from Implement Consulting Group’s uncompromising focus on Change with Impact – with the aim of setting change processes in motion and thus achieving measurable impact together with clients.

Over the course of the last few years, Implement has concluded that for Change with Impact to happen, the integration of employee potential is indispensable. Companies must consistently position their organisation in such a way that they are fit for humans and fit for the future, Implement was able to contribute experience from its own consulting practice as well as the company itself in an intensive exchange during the research work for the book Humanocracy by Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini – a contribution that is acknowledged in the book itself.

The various authors of this research series are experts in the fields of strategy and innovation, commercial excellence and agile organisation and bring their combined expertise of many years to bear in customised projects for clients.

Implement Consulting Group was founded in 1996, is shaped by 1400 people and is owned by 250 people. The fast-growing, international consulting company with Scandinavian roots has a worldwide presence and 9 offices around the world.

References

Hamel, G. & Zanini, M. (2020): Humanocracy: Creating Organizations as Amazing as the People Inside Them. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Denning, S. (2018): The Age of Agile: How Smart Companies Are Transforming the Way Work Gets Done. New York, NY: AMACOM.

McGrath, R. (2019): Seeing Around Corners: How to Spot Inflection Points in Business Before They Happen. Boston, MA: Mariner Books.

Hill, L. (2014): Collective Genius: The Art and Practice of Leading Innovation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Schaefer, M.W. (2019): Marketing Rebellion: The Most Human Company Wins. Louisville, TN: Schaefer Marketing Solutions.